Newton's laws of motion are three physical laws that, together, laid the foundation for classical mechanics. They describe the relationship between a body and the forces acting upon it, and its motion in response to those forces. More precisely, the first law defines the force qualitatively, the second law offers a quantitative measure of the force, and the third asserts that a single isolated force doesn't exist. These three laws have been expressed in several ways, over nearly three centuries, and can be summarised as follows:

|

First law: |

In an inertial frame of reference, an object either remains at rest or continues to move at a constant velocity, unless acted upon by force. |

|

Second law: |

In an inertial frame of reference, the vector sum of the forces F on an object is equal to the mass m of that object multiplied by the acceleration a of the object: F = ma. (It is assumed here that the mass m is constant – see below.) |

|

Third law: |

When one body exerts a force on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction on the first body. |

The three laws of motion were first compiled by Isaac Newton in his Philosophić Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), first published in 1687. Newton used them to explain and investigate the motion of many physical objects and systems. For example, in the third volume of the text, Newton showed that these laws of motion, combined with his law of universal gravitation, explained Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

Some also describe a fourth law which states that forces add up like vectors, that is, that forces obey the principle of superposition.

Overview

Newton's laws are applied to objects which are idealised as single point masses, in the sense that the size and shape of the object's body are neglected to focus on its motion more easily. This can be done when the object is small compared to the distances involved in its analysis, or the deformation and rotation of the body are of no importance. In this way, even a planet can be idealised as a particle for analysis of its orbital motion around a star.

In their original form, Newton's laws of motion are not adequate to characterise the motion of rigid bodies and deformable bodies. Leonhard Euler in 1750 introduced a generalisation of Newton's laws of motion for rigid bodies called Euler's laws of motion, later applied as well for deformable bodies assumed as a continuum. If a body is represented as an assemblage of discrete particles, each governed by Newton's laws of motion, then Euler's laws can be derived from Newton's laws. Euler's laws can, however, be taken as axioms describing the laws of motion for extended bodies, independently of any particle structure.

Newton's laws hold only with respect to a certain set of frames of reference called Newtonian or inertial reference frames. Some authors interpret the first law as defining what an inertial reference frame is; from this point of view, the second law holds only when the observation is made from an inertial reference frame, and therefore the first law cannot be proved as a special case of the second. Other authors do treat the first law as a corollary of the second. The explicit concept of an inertial frame of reference was not developed until long after Newton's death.

In the given interpretation mass, acceleration, momentum, and (most importantly) force are assumed to be externally defined quantities. This is the most common, but not the only interpretation of the way one can consider the laws to be a definition of these quantities.

Newtonian mechanics has been superseded by special relativity, but it is still useful as an approximation when the speeds involved are much slower than the speed of light.

Laws

Newton's laws read:

Law I: Every body persists in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by force impressed.

Law II: The alteration of motion is ever proportional to the motive force impress'd; and is made in the direction of the right line in which that force is impress'd.

Law III: To every action there is always opposed an equal reaction: or the mutual actions of two bodies upon each other are always equal, and directed to contrary parts.

Newton's first law

Main article: Inertia

The first law states that if the net force (the vector sum of all forces acting on an object) is zero, then the velocity of the object is constant. Velocity is a vector quantity which expresses both the object's speed and the direction of its motion; therefore, the statement that the object's velocity is constant is a statement that both its speed and the direction of its motion are constant.

The first law can be stated mathematically when the mass is a non-zero constant, as,

![]()

Consequently,

· An object that is at rest will stay at rest unless a force acts upon it.

· An object that is in motion will not change its velocity unless a force acts upon it.

This is known as uniform motion. An object continues to do whatever it happens to be doing unless a force is exerted upon it. If it is at rest, it continues in a state of rest (demonstrated when a tablecloth is skilfully whipped from under dishes on a tabletop and the dishes remain in their initial state of rest). If an object is moving, it continues to move without turning or changing its speed. This is evident in space probes that continuously move in outer space. Changes in motion must be imposed against the tendency of an object to retain its state of motion. In the absence of net forces, a moving object tends to move along a straight line path indefinitely.

Newton placed the first law of motion to establish frames of reference for which the other laws are applicable. However, Newton implicitly referred to the absolute co-ordinate of cosmos for this frame. Since we cannot precisely measure our velocity relative to a far star, Newton's frame is based on a pure imagination, not based on measurable physics. In current physics, an observer defines himself as in inertial frame by preparing one stone hooked by a spring, and rotating the spring to any direction, and observing the stone static and the length of that spring unchanged. By Einstein's equivalence principle, if there was one such observer A and another observer B moving in a constant velocity related to A, then A and B will both observe the same physics phenomena. if A verified the first law, then B will verify it too. In this way, the definition of inertial can get rid of absolute space or far star, and only refer to the objects locally reachable and measurable.

A particle not subject to forces moves (related to inertial frame) in a straight line at a constant speed. Newton's first law is often referred to as the law of inertia. Thus, a condition necessary for the uniform motion of a particle relative to an inertial reference frame is that the total net force acting on it is zero. In this sense, the first law can be restated as:

In every material universe, the motion of a particle in a preferential reference frame Φ is determined by the action of forces whose total vanished for all times when and only when the velocity of the particle is constant in Φ. That is, a particle initially at rest or in uniform motion in the preferential frame Φ continues in that state unless compelled by forces to change it.

Newton's first and second laws are valid only in an inertial reference frame. Any reference frame that is in uniform motion with respect to an inertial frame is also an inertial frame, i.e. Galilean invariance or the principle of Newtonian relativity.

Newton's second law

The second law states that the rate of change of momentum of a body is directly proportional to the force applied, and this change in momentum takes place in the direction of the applied force.

![]()

The second law can also be stated in terms of an object's acceleration. Since Newton's second law is valid only for constant-mass systems, m can be taken outside the differentiation operator by the constant factor rule in differentiation. Thus,

![]()

where F is the net force applied, m is the mass of the body, and a is the body's acceleration. Thus, the net force applied to a body produces a proportional acceleration. In other words, if a body is accelerating, then there is a force on it. An application of this notation is the derivation of G Subscript C.

The above statements hint that the second law is merely a definition of F, not a precious observation of nature. However, current physics restate the second law in measurable steps: (1)defining the term 'one unit of mass' by a specified stone, (2)defining the term 'one unit of force' by a specified spring with specified length, (3)measuring by experiment or proving by theory (with a principle that every direction of space are equivalent), that force can be added as a mathematical vector, (4)finally conclude that These steps hint the second law is a precious feature of nature.

The second law also implies the conservation of momentum: when the net force on the body is zero, the momentum of the body is constant. Any net force is equal to the rate of change of the momentum.

Any mass that is gained or lost by the system will cause a change in momentum that is not the result of an external force. A different equation is necessary for variable-mass systems (see below).

Newton's second law is an approximation that is increasingly worse at high speeds because of relativistic effects.

According to modern ideas of how Newton was using his terminology, the law is understood, in modern terms, as an equivalent of:

The change of momentum of a body is proportional to the impulse impressed on the body, and happens along the straight line on which that impulse is impressed.

This may be expressed by the formula F = p', where p' is the time derivative of the momentum p. This equation can be seen clearly in the Wren Library of Trinity College, Cambridge, in a glass case in which Newton's manuscript is open to the relevant page.

Motte's 1729 translation of Newton's Latin continued with Newton's commentary on the second law of motion, reading:

If a force generates a motion, a double force will generate double the motion, a triple force triple the motion, whether that force be impressed altogether and at once, or gradually and successively. And this motion (being always directed the same way with the generating force), if the body moved before, is added to or subtracted from the former motion, according as they directly conspire with or are directly contrary to each other; or obliquely joined, when they are oblique, so as to produce a new motion compounded from the determination of both.

The sense or senses in which Newton used his terminology, and how he understood the second law and intended it to be understood, have been extensively discussed by historians of science, along with the relations between Newton's formulation and modern formulations.

Impulse

An impulse J occurs when a force F acts over an interval of time Δt, and it is given by

Since force is the time derivative of momentum, it follows that

![]()

This relation between impulse and momentum is closer to Newton's wording of the second law.

Impulse is a concept frequently used in the analysis of collisions and impacts.

Variable-mass systems

Main article: Variable-mass system

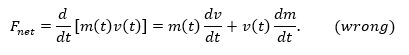

Variable-mass systems, like a rocket burning fuel and ejecting spent gases, are not closed and cannot be directly treated by making mass a function of time in the second law; that is, the following formula is wrong:

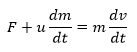

The falsehood of this formula can be seen by noting that it does not respect Galilean invariance: a variable-mass object with F = 0 in one frame will be seen to have F ≠ 0 in another frame. The correct equation of motion for a body whose mass m varies with time by either ejecting or accreting mass is obtained by applying the second law to the entire, constant-mass system consisting of the body and its ejected/accreted mass; the result is

where u is the velocity of the escaping or incoming mass relative to the body. From this equation one can derive the equation of motion for a varying mass system, for example, the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation. Under some conventions, the quantity u dm/dt on the left-hand side, which represents the advection of momentum, is defined as a force (the force exerted on the body by the changing mass, such as rocket exhaust) and is included in the quantity F. Then, by substituting the definition of acceleration, the equation becomes F = ma.

Newton's third law

The third law states that all forces between two objects exist in equal magnitude and opposite direction: if one object A exerts a force FA on a second object B, then Bsimultaneously exerts a force FB on A, and the two forces are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction: FA = −FB. The third law means that all forces are interactions between different bodies, or different regions within one body, and thus that there is no such thing as a force that is not accompanied by an equal and opposite force. In some situations, the magnitude and direction of the forces are determined entirely by one of the two bodies, say Body A; the force exerted by Body A on Body B is called the "action", and the force exerted by Body B on Body A is called the "reaction". This law is sometimes referred to as the action-reaction law, with FA called the "action" and FB the "reaction". In other situations the magnitude and directions of the forces are determined jointly by both bodies and it isn't necessary to identify one force as the "action" and the other as the "reaction". The action and the reaction are simultaneous, and it does not matter which is called the action and which is called reaction; both forces are part of a single interaction, and neither force exists without the other.

The two forces in Newton's third law are of the same type (e.g., if the road exerts a forward frictional force on an accelerating car's tires, then it is also a frictional force that Newton's third law predicts for the tires pushing backward on the road).

From a conceptual standpoint, Newton's third law is seen when a person walks: they push against the floor, and the floor pushes against the person. Similarly, the tires of a car push against the road while the road pushes back on the tires—the tires and road simultaneously push against each other. In swimming, a person interacts with the water, pushing the water backward, while the water simultaneously pushes the person forward—both the person and the water push against each other. The reaction forces account for the motion in these examples. These forces depend on friction; a person or car on ice, for example, may be unable to exert the action force to produce the needed reaction force.

Newton used the third law to derive the law of conservation of momentum; from a deeper perspective, however, conservation of momentum is the more fundamental idea (derived via Noether's theorem from Galilean invariance), and holds in cases where Newton's third law appears to fail, for instance when force fields as well as particles carry momentum, and in quantum mechanics.